Health Topics

Stress urinary incontinence occurs when your bladder leaks urine during physical activity or exertion. It may happen when you cough, sneeze, lift something heavy, change positions, or exercise.

Causes

Stress incontinence occurs when the tissue that supports your urethra gets weak.

- The bladder and urethra are supported by the pelvic floor muscles. Urine flows from your bladder through your urethra to the outside.

- The urinary sphincter is a muscle around the opening of the bladder. It squeezes to prevent urine from leaking through the urethra.

When either set of muscles become weak, urine can pass when pressure is placed on your bladder. You may notice it when you:

- Cough

- Sneeze

- Laugh

- Exercise

- Lift heavy objects

- Have sex

Weakened pelvic floor muscles may be caused by:

- Childbirth

- Injury to the urethra area

- Some medicines

- Surgery in the pelvic area or the prostate (in men)

- Being overweight

- Unknown causes

Stress incontinence is common in women. Some things increase your risk, such as:

- Pregnancy and vaginal delivery.

- Pelvic prolapse. This is when your bladder, urethra, or rectum slide into the vagina. Delivering a baby can cause nerve or tissue damage in the pelvic area. This can lead to pelvic prolapse months or years after delivery.

Symptoms

The main symptom of stress incontinence is leaking urine when you:

- Are physically active

- Cough or sneeze

- Exercise

- Stand from a sitting or lying down position

Exams and Tests

Your health care provider will perform a physical exam. This will include:

- Genital exam in men

- Pelvic exam in women

- Rectal exam

Tests may include:

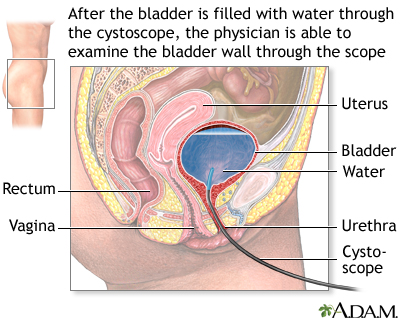

- Cystoscopy to look inside the bladder.

- Pad weight test: You exercise while wearing a sanitary pad. Then the pad is weighed to find out how much urine you lost.

- Voiding diary: You track your urinary habits, leakage and fluid intake.

- Pelvic or abdominal ultrasound.

- Post-void residual (PVR) to measure the amount of urine left after you urinate.

- Urinalysis to check for urinary tract infection.

- Urinary stress test: You stand with a full bladder and then cough.

- Urodynamic studies to measure pressure and urine flow.

- X-rays with contrast dye to look at your kidneys and bladder.

Treatment

Treatment depends on how your symptoms affect your life.

There are 3 types of treatment for stress incontinence:

- Behavior changes and bladder training

- Pelvic floor muscle training

- Surgery

There are no medicines for treatment of stress incontinence. Some providers may prescribe a medicine called duloxetine. This medicine is not approved by FDA for the treatment of stress incontinence.

BEHAVIOR CHANGES

Making these changes may help:

- Drink less fluid (if you drink more than normal amounts of fluid). Avoid drinking water before going to bed.

- Avoid jumping or running.

- Take fiber to avoid constipation, which can make stress urinary incontinence worse.

- Quit smoking. This can reduce coughing and bladder irritation. Smoking also increases your risk for bladder cancer.

- Avoid alcohol and caffeinated drinks such as coffee. They can make your bladder fill up quicker.

- Lose excess weight.

- Avoid foods and drinks that may irritate your bladder. These include spicy foods, carbonated drinks, and citrus.

- If you have diabetes, keep your blood sugar under good control.

BLADDER TRAINING

Bladder training may help you control your bladder. You will be asked to urinate at regular intervals. Slowly, the time interval is increased. This causes the bladder to stretch and hold more urine.

PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING

There are different ways to strengthen the muscles in your pelvic floor.

- Biofeedback: This method can help you learn to identify and control your pelvic floor muscles.

- Kegel exercises: These exercises can help keep the muscle around your urethra strong and working well. This may help keep you from leaking urine.

- Vaginal cones: You place the cone into the vagina. Then you try to squeeze your pelvic floor muscles to hold the cone in place. You can wear the cone for up to 15 minutes at a time, two times a day. You may notice improvement in your symptoms in 4 to 6 weeks.

- Pelvic floor physical therapy: Physical therapists specially trained in the area can fully evaluate the problem and help with exercises and therapies.

SURGERIES

If other treatments do not work, your provider may suggest surgery. Surgery may help if you have bothersome stress incontinence. Most providers suggest surgery only after trying nonsurgical treatments.

- Anterior vaginal repair helps restore weak and sagging vaginal walls. This is used when the bladder bulges into the vagina (prolapse). Prolapse may be associated with stress urinary incontinence.

- Artificial urinary sphincter: This is a device used to keep urine from leaking. It is used mainly in men. It is rarely used in women.

- Bulking injections make the area around the urethra thicker. This helps control leakage. The procedure may need to be repeated after a few months or years.

- Urethral sling is a mesh tape used to put pressure on the urethra. It can be used in men and women. It is easier to do than placing an artificial urinary sphincter.

- Retropubic suspensions lift the bladder and urethra. This is done less often due to the frequent use and success with urethral slings.

Outlook (Prognosis)

Getting better takes time, so try to be patient. Symptoms most often get better with nonsurgical treatments. However, they will not cure stress incontinence. Surgery can cure most people of stress incontinence.

Treatment does not work as well if you have:

- Conditions that prevent healing or make surgery more difficult

- Other genital or urinary problems

- Past surgery that did not work

- Poorly controlled diabetes

- Neurologic disease

- Previous radiation to the pelvis

Possible Complications

Physical complications are rare and most often mild. They can include:

- Irritation of the vagina lips (labia and vulva)

- Skin sores or pressure ulcers in people who have incontinence and can't get out of the bed or chair

- Unpleasant odors

- Urinary tract infections

The condition may get in the way of social activities, careers, and relationships. It also may lead to:

- Embarrassment

- Isolation

- Depression or anxiety

- Loss of productivity at work

- Loss of interest in sexual activity

- Sleep disturbances

Complications associated with surgery include:

- Fistulas or abscesses

- Bladder or intestine injury

- Bleeding

- Infection

- Urinary incontinence -- if you have trouble urinating you may need to use a catheter. This is often temporary

- Pain during intercourse

- Sexual dysfunction

- Wearing away of materials placed during surgery, such as a sling or artificial sphincter

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your provider if you have symptoms of stress incontinence and they bother you.

Prevention

Doing Kegel exercises may help prevent symptoms. Women may want to do Kegels during and after pregnancy to help prevent incontinence.

Alternative Names

Incontinence - stress; Bladder incontinence stress; Pelvic prolapse - stress incontinence; Stress incontinence; Leakage of urine - stress incontinence; Urinary leakage - stress incontinence; Pelvic floor - stress incontinence

Patient Instructions

- Indwelling catheter care

- Kegel exercises - self-care

- Self catheterization - female

- Sterile technique

- Urinary catheters - what to ask your doctor

- Urinary incontinence products - self-care

- Urinary incontinence surgery - female - discharge

- Urinary incontinence - what to ask your doctor

- Urine drainage bags

- When you have urinary incontinence

References

Al-Mousa RT, Hashim H. Evaluation and management of men with urinary incontinence. In: Partin AW, Dmochowski RR, Kavoussi LR, Peters CA, eds. Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 113.

Kobashi KC, Vasavada S, Bloschichak A, et al. Updates to surgical treatment of female stress urinary incontinence (SUI): AUA/SUFU Guideline (2023). J Urol. 2023;209(6):1091-1098 PMID: 37096580 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37096580/.

Lucioni A, Kobashi KC. Evaluation and management of women with urinary incontinence and pelvic prolapse. In: Partin AW, Dmochowski RR, Kavoussi LR, Peters CA, eds. Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 112.

Patton S, Bassaly RM. Urinary incontinence. In: Kellerman RD, Rakel DP, Heidelbaugh JJ, Lee EM, eds. Conn's Current Therapy 2024. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:1201-1203.

Resnick NM, DuBeau CE. Urinary incontinence. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 115.

Review Date 3/31/2024

Updated by: Sovrin M. Shah, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Urology, The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.