Health Topics

4 discoveries beyond the brain

NIH research explores early signs of brain disorders

Neurodegenerative diseases—such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease (PD), Lewy body dementia (LBD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (also known as ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease)—affect millions of people around the world. These conditions progressively damage nerve cells in the brain and nervous system. Over time, this can lead to problems with movement, thinking, memory, and more.

A century ago, many neurological conditions could only be diagnosed through an autopsy (after the person had died). Fortunately, today’s doctors and scientists have more ways to examine the brains and nervous systems of living patients. But these disorders can still be challenging to detect. Current diagnostic tools often identify these diseases after they have already started to damage the brain.

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) leads research to help better understand, diagnose, and treat these conditions. Here are four recent discoveries that may help doctors and scientists spot early signs of damage, develop and test new treatments, and figure out who might benefit most from specific therapies.

Heart imaging reveals early signs

NINDS researchers at the NIH Clinical Center used a new method to identify early signs of PD and LBD. This team used a special type of PET scan to look at the hearts of people at high risk for these diseases. They found that people who later developed PD or LBD had levels of a chemical called norepinephrine in their hearts that were much lower than is typical, years before they showed any symptoms.

These findings suggest that PD or LBD might start in the part of the nervous system that controls automatic body functions (like heart rate and blood pressure) even before they affect the brain. Being able to spot these early signs could change how doctors understand and treat these diseases.

Blood tests for mitochondrial damage

NIH-funded researchers are developing a blood test that measures the level of damage to the DNA inside mitochondria—the cell’s energy producers. Previous research suggests that mitochondrial damage may be linked to some cases of PD, so focusing on this damage may help identify and diagnose PD early on. In this study, blood samples from people with PD showed more cell damage compared to samples from healthy volunteers. Some people with PD also had more damage than others.

Researchers still need to show that the test works in larger and more diverse populations. If successful, the test could help identify treatments that target mitochondria, learn which patients are most likely to respond to certain treatments, and determine whether a treatment is working.

Artificial intelligence analyzes sleep breathing patterns

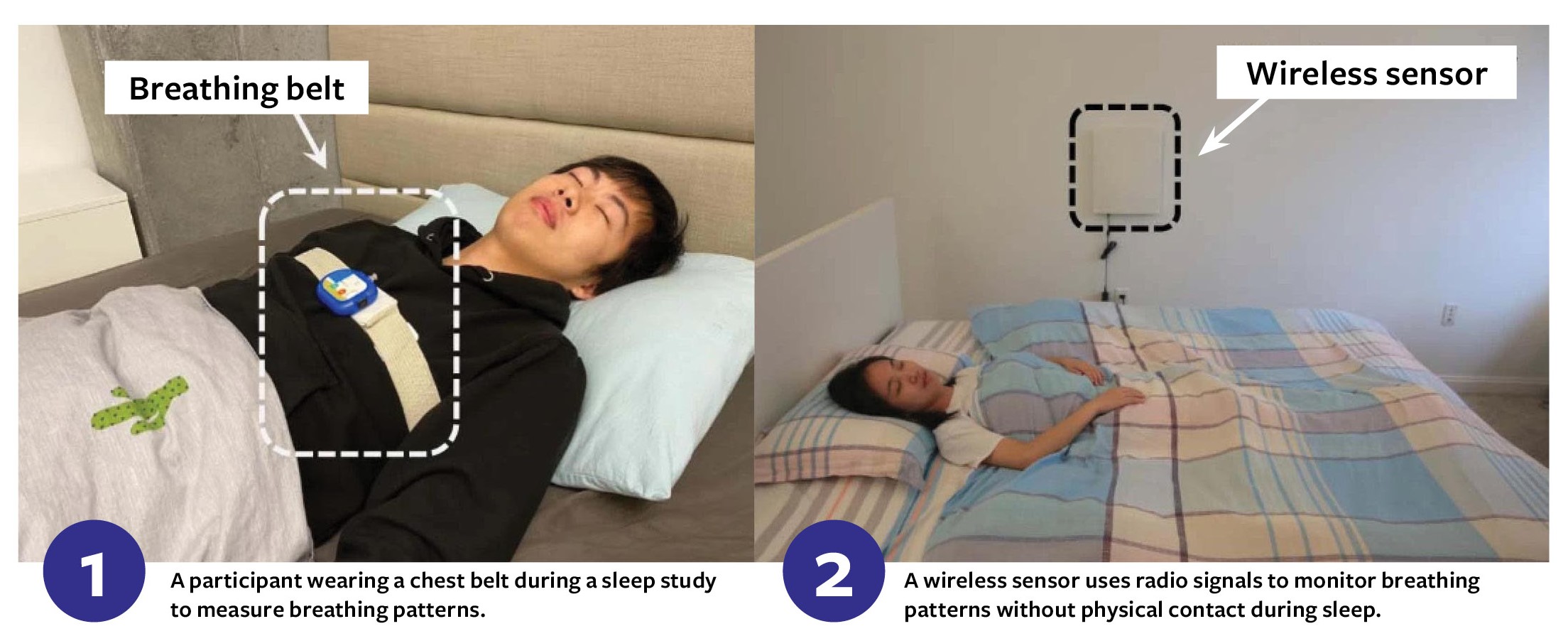

In another innovative study, NINDS-funded researchers used an artificial intelligence (AI) program to identify PD by analyzing breathing patterns during sleep. The researchers tested the AI program using two types of sleep data: breathing patterns and brain activity.

By looking at 12 nights of sleep test data from people with and without PD, the program was able to identify those with PD with a high degree of accuracy. It also detected small changes in PD symptoms over a longer period of time more accurately than traditional clinical assessments.

This program could help both doctors and researchers. By using this tool, doctors may find PD earlier, and researchers may develop new treatments easier and faster. However researchers need to test it with more people from diverse backgrounds first. They also think it could be especially helpful for people who live in remote areas or have trouble leaving home.

Top: A participant wearing a chest belt during a sleep study to measure breathing patterns. Bottom: A wireless sensor uses radio signals to monitor breathing patterns without physical contact during sleep.

Image 1: A participant wearing a chest belt during a sleep study to measure breathing patterns. Image 2: A wireless sensor uses radio signals to monitor breathing patterns without physical contact during sleep.

Skin biopsy for neurodegenerative diseases

NIH-funded researchers developed a simple skin biopsy that may identify people with PD, LBD, and related disorders. This quick, nearly painless test looks for phosphorylated alpha-synuclein, a specific protein that’s associated with certain neurodegenerative diseases.

In this study, researchers looked at small skin samples from people diagnosed with one of these conditions and people without any history of neurodegenerative diseases. The test found this protein in more than 90% of people with a diagnosis compared to only 3% of individuals without one. This could lead to faster, more accurate diagnoses and earlier treatments for patients.