Health Topics

Audio analgesia: How sound blunts pain—at least in mice

Music can make you feel better on a bad day, but can it literally take your pain away? Research suggests that music—and sound in general—may have the power to do just that.

An international team of scientists, led in part by investigators from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, studied mice to understand how this process works. Their findings could open the door to new, safer ways to treat pain in humans.

Music can take your pain away

Since the 1960s, music and other sounds have been found to ease pain from a range of different health conditions and procedures. Research shows that sound can reduce the pain of dental extractions, sickle cell disease, and childbirth, among others.

According to Yuanyuan “Kevin” Liu, Ph.D., an investigator for the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), music can grab our attention and help us relax. But his team’s recent findings suggest the analgesic (pain-reducing) effect is from sound rather than music specifically. Dr. Liu studies sensory biology and pain. He is especially interested in the relationship between the mind and body and the role that perceptions play in this relationship.

To find out how sound dulls pain, Dr. Liu and a group of researchers in the United States and China turned to unlikely research subjects: mice with inflamed paws.

Playing Bach for mice

For three days in a row, Dr. Liu and his team exposed the mice to three different sounds:

- Harmonious classical music (composed by Bach)

- Inharmonious music (an unpleasant rearrangement of the same Bach piece)

- Background/white noise

The researchers used a technique to measure and compare the mice’s pain sensitivity before and after hearing the sounds.

All three kinds of sound reduced the mice’s pain. Surprisingly, the harmonious music was no more or less effective than the other sounds. The sounds also only reduced pain when played at very low intensities―just above a whisper. When the intensity increased, these effects disappeared.

Signal to the sound

Dr. Liu explained that it was not the sound’s volume itself but rather the signal-to-noise ratio―the sound’s intensity compared to the background noise. The sweet spot for pain relief was just above the level of the background noise.

Dr. Liu compared this to using background music played at a low volume, which he does when he needs to concentrate: “Just a little bit of sound, not too loud. Maybe that’s the magic?”

Pain reduced for days

Stress, attention, and emotions are all involved in pain perception. When you hear music, for example, your attention temporarily shifts toward the sound and away from your pain. The mice heard the sounds for just 20 minutes a day for three days. But the pain-reducing effect lasted for several days after, which Dr. Liu said can’t be explained by a shift in attention alone.

Stress reduction is another possible explanation, but the researchers did not see changes in the mice’s stress hormones and behaviors after hearing the sounds. This suggested that something else was happening.

Pathways in the brain

Brain imaging studies in humans show that music can affect areas in the brain related to pain processing but not which specific neural networks are involved.

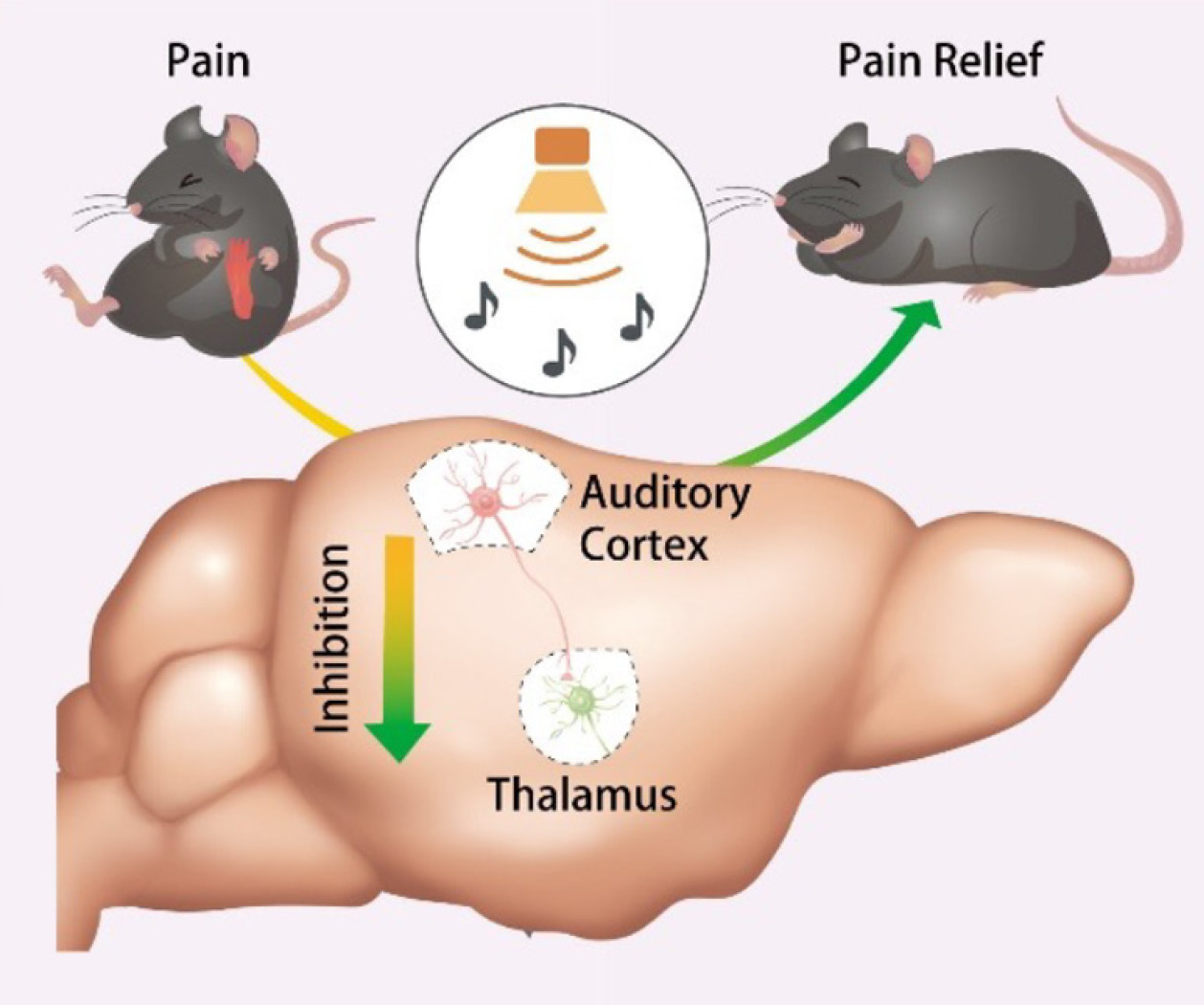

To find out, the researchers used imaging to trace neural activity in the mice’s brains when they heard the sounds. They discovered a direct pathway between the part of the brain that receives and processes information about sound (called the auditory cortex) and the thalamus, which also receives information about sensations such as pain.

Dr. Liu described the thalamus as the brain’s sensory information hub. All kinds of sensory information from inside and outside the body―including sound―come together in the thalamus, which affects how we experience or perceive that information. The low-intensity sound appeared to disrupt pain signaling in this pathway, making the mice less sensitive to pain.

Because the brain has a hard time processing input from different sensory systems at the same time, Dr. Liu said that lowering activity in the neurons in this pathway may be a way to manage some of these competing messages.

How it works

Sound comes in through your ear to your auditory cortex, which has a direct line of communication with the thalamus. Similarly, pain receptors in the body send messages about sensations like pressure and temperature through the spinal cord to the thalamus.The thalamus takes in information from different senses and sends messages about them to other parts of the brain.

What it all means

Understanding how processes in the brain regulate pain could help researchers develop new pain therapies in the future. Will your doctor start prescribing bluegrass, jazz, or classic rock tunes to ease your pain? Probably not any time soon. While these findings show how mice’s brains regulate pain in response to sound, our brains may process and regulate pain in different ways. For example, Dr. Liu explained, humans have emotional connections to sounds such as music, and those connections are different for each person. Mice may also respond emotionally to different kinds of sound, but they do not have the language to tell us.

Dr. Liu said he wonders what roles other sensory processes might play in how we experience pain. If sound can affect our perception of pain, can light do the same thing? Researchers are exploring these questions and more, leading us closer to exciting new pain relief strategies.

NIDCR researchers found that low-intensity sound makes mice less sensitive to pain by disrupting pain signaling in the brain’s pathway between the auditory cortex and thalamus.