Health Topics

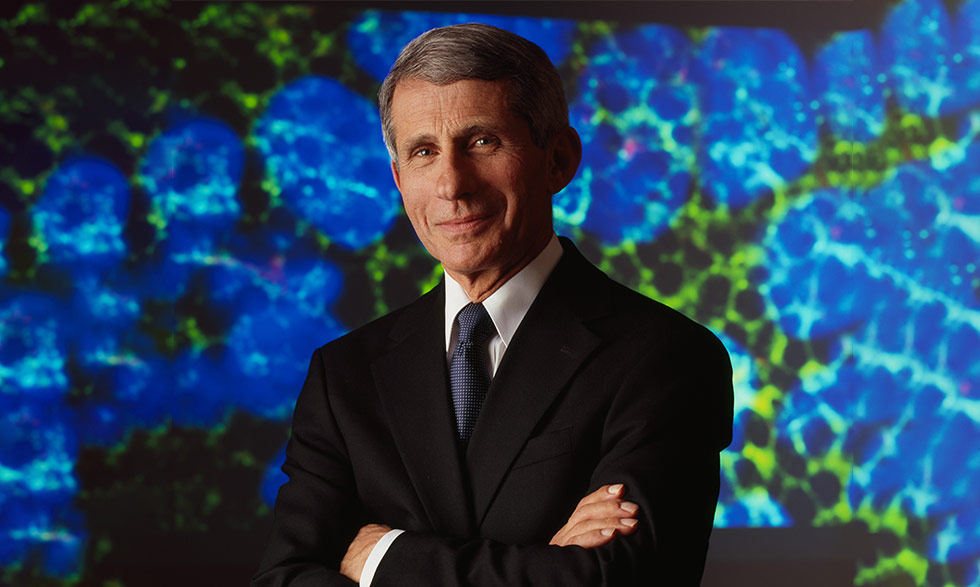

NIH's Dr. Fauci on the COVID-19 battle

NIAID director talks virus variants and careers in public health

Anthony S. Fauci, M.D., director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), is no stranger to pandemics or infectious diseases. He has served as NIAID's director since 1984 and has worked there for more than five decades.

One important skill he has brought to the COVID‐19 pandemic response is his ability to explain complex health information in clear, actionable ways. "If people really want to know what's going on," says National Institutes of Health (NIH) Director Francis S. Collins, M.D., Ph.D., "they know that Tony's going to tell them those facts, even if they're not the facts that everybody necessarily wants to hear." Dr. Fauci recently sat down to talk about the latest COVID-19 facts and science, focusing on how new variants of the virus might affect the public, especially when it comes to vaccines.

You and Dr. Collins were recently vaccinated against COVID-19 here at NIH. How was that experience?

After the first dose, my arm, about seven hours after the vaccination, felt a bit achy. That lasted until the following day, and toward the end of the second day, it was completely gone. And that was great. Twenty-eight days later, we got the boost. That was a little bit different. I felt a little achy but not anything that interfered with my going to work or functioning on my typical 17-hour day. It didn't bother me. However, when I got home that evening, I felt chilly. I don't think I had a fever at all, but I felt chilly. So, a combination of 24 hours of the arm hurting again, a little bit of a fatigue, a little bit of a muscle ache, a little chilliness, and then by the afternoon of the second day, it was completely gone.

Why is it essential for people to get the vaccine?

That's really very important. First of all, we're dealing with a vaccine that has a 94% to 95% efficacy, and virtually 100% efficacy against severe disease, like hospitalization and death. So, the vaccine is extremely important, for your own health, for the health of your family, and for those around you who might be in a situation where they have underlying conditions. It's also important for society in general, because the more people who get vaccinated, the closer you're going to get to what's called herd immunity. Namely, if we get about 70% to 75% of the population vaccinated, we're going to have such an umbrella of protection in society that the virus won't have anywhere to go. It would not be able to find any susceptible people.

Do you still need to wear a mask in public after you've been vaccinated?

If you have been fully vaccinated, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)'s guidance now says you can resume most activities outdoors and indoors that you took part in prior to the pandemic without wearing a mask, except where masking is required by state, local, tribal, or territorial laws, rules, and regulations. You still need to follow rules of your workplace and local businesses. The CDC still advises travelers to wear masks while on airplanes, buses, or trains, and calls for wearing masks in some indoor settings, including hospitals, homeless shelters, and prisons. Masks are required in these settings as it is conceivable that you could be vaccinated and get infected but not know it, because the vaccine is protecting you against symptoms. You still might have some virus in your nasopharynx [upper part of your throat, behind your nose] that could infect unvaccinated or other vulnerable people in congregate settings.

What is a COVID-19 variant, and how is NIH studying and tracking these variants?

There are a lot of terms that sometimes get interchanged—variant, strain, lineage—they all really mean the same thing. As SARS-CoV-2 replicates, changes in its genome (often called a mutation) can occur, and some result in a change in an amino acid that makes up a viral protein. Most mutations don't have any functional impact on the virus, but every once in a while, you get a constellation of mutations that does have significance in one way or another. This is often referred to as a variant. Some of these variants can spread more easily or have the potential to be resistant to particular treatments or vaccines. These are the variants that we are watching very closely.

Multiple variants of the virus that causes COVID-19 have been documented in the U.S. and globally during this pandemic. We are monitoring multiple variants; currently there are six notable variants in the U.S., some that seem to spread more easily and quickly than other variants. So far, studies suggest that our currently authorized vaccines work against the circulating variants. The Alpha variant, also known as B.1.1.7, was first recognized in the United Kingdom and is now the most common variant in the U.S., surpassing in prevalence the original viruses that originally entered this country. Cases of COVID-19 caused by other variants first seen in other parts of the world have occurred in relatively small numbers in this country.

We are keeping a close eye on all of these, especially the Beta (B.1.351), Gamma (P.1), and Delta (B.1617.2) variants that may be able to evade the immune system and certain antibody therapies to a greater extent than the original virus and other variants. To be sure that we don't get caught behind the eight ball, companies are already making variations of the vaccine directed against certain variant strains.

The pandemic has inspired many people to consider careers in public health. What advice do you have for an interested young person or professional? How do they become the next Dr. Fauci?

If public health, and science, and medicine, is something that you might even have the slightest inclination to pursue, I strongly encourage young people to pursue it. It really has to be one of the most exciting careers you could possibly imagine, if it suits you. The reason is, it combines science and health in a way that has enormously broad implications.

When I graduated from medical school and did multiple years of residency, including a chief residency and then a fellowship in infectious diseases, I was taking care of individual patients. It was very exciting. I still see individual patients. But the excitement and the thrill you get when you're working on something that has implications for millions if not billions of people, I mean, there can be nothing more exciting than that.

Everything that we do, all of us, from NLM to NIAID to any of the other 25 institutes and centers, all of us who get involved in that are having an impact, literally, on billions of people. So, when I see a young person who has even the slightest interest, I say, you better pursue it, because you're not going to imagine how exciting this could be.

What are some lessons we have learned from this pandemic?

Well, there are always lessons that are learned, if you do it right, from one [pandemic] to another.

I think one of the things that really was [evident] was the importance of the chain of fundamental basic and clinical research. I mean, to be able to use the fundamental structural biology that we focused on with HIV, the same investigators collaborated with each other and used that structure-based vaccine design. That never would have happened if we hadn't had fundamental basic research that started off decades ago. So, to me, that's such a good example of the need to continue to fund fundamental basic research.

![Dr. Fauci and Dr. Clifford Lane [M.D.] discussing AIDS-related data in 1987.](https://magazine.medlineplus.gov/images/uploads/main_images/dr-fauci-dr-lane-HIV.jpg)

But then there are a lot of, also, public health lessons learned: the importance of a global health strategic network and surveillance, especially the ability to do rapid, extensive, comprehensive genomic surveillance.

Are there any NIH-specific sources you can recommend for people looking for trusted health information?

Well, particularly when you're dealing with clinical trials, I think ClinicalTrials.gov, GenBank, and then [especially for scientists and researchers] the National Library of Medicine (NLM)'s PubMed, which I use 20 times a day.

Do you have a final message that you would like to convey to the public?

This is a global pandemic, and it needs to be addressed at a global level. So, we should concentrate not only on controlling it in our own country, but we've got to control it globally, otherwise it's going to continue to come back to the U.S. with mutants and new versions of the virus. So, it will end, but it will end depending upon the effort that we put into it.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. For the latest COVID-19 guidance, visit the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website.