Health Topics

Mitral stenosis is a disorder in which the mitral valve does not fully open. This restricts the flow of blood.

Causes

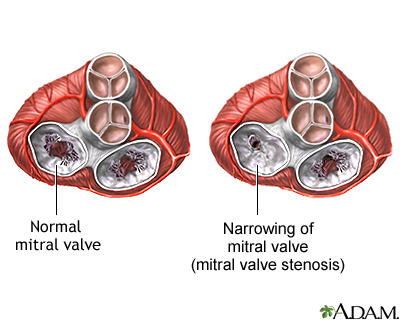

Blood that flows between different chambers of your heart must flow through a valve. The valve between the 2 chambers on the left side of your heart is called the mitral valve. It opens up enough so that blood can flow from the upper chamber of your heart (left atrium) to the lower chamber (left ventricle). It then closes, keeping blood from flowing backwards.

Mitral stenosis means that the valve cannot open enough. As a result, less blood flows to the body. The upper heart chamber swells as pressure builds up. Blood and fluid may then collect in the lung tissue (pulmonary edema), making it hard to breathe.

In adults, mitral stenosis occurs most often in people who have had rheumatic fever. This is a disease that can develop after an illness with strep throat that was not properly treated.

The valve problems develop 5 to 10 years or more after having rheumatic fever. Symptoms may not show up for even longer. Rheumatic fever is rare in the United States because strep infections are most often treated. This has made mitral stenosis less common.

Rarely, other factors can cause mitral stenosis in adults. These include:

- Calcium deposits forming around the mitral valve

- Radiation treatment to the chest

- Some medicines

Children may be born with mitral stenosis (congenital) or other birth defects involving the heart that cause mitral stenosis. Often, there are other heart defects present along with the mitral stenosis.

Mitral stenosis may run in families.

Symptoms

Adults may have no symptoms. However, symptoms may appear or get worse with exercise or other activity that raises the heart rate. Symptoms will most often develop between ages 20 and 50.

Symptoms may begin with an episode of atrial fibrillation (especially if it causes a fast heart rate). Symptoms may also be triggered by pregnancy or other stress on the body, such as infection in the heart or lungs, or other heart disorders.

Symptoms may include:

- Chest discomfort that increases with activity and extends to the arm, neck, jaw or other areas (this is rare)

- Cough, possibly with bloody phlegm

- Difficulty breathing during or after exercise (This is the most common symptom.)

- Waking up due to breathing problems or when lying in a flat position

- Fatigue

- Frequent respiratory infections, such as bronchitis

- Feeling of pounding heart beat (palpitations)

- Swelling of feet or ankles

In infants and children, symptoms may be present from birth (congenital). They will almost always develop within the first 2 years of life. Symptoms include:

- Cough

- Poor feeding, or sweating when feeding

- Poor growth

- Shortness of breath

Exams and Tests

The health care provider will listen to the heart and lungs with a stethoscope. A murmur, snap, or other abnormal heart sound may be heard. The typical murmur is a rumbling sound that is heard over the heart during the resting phase of the heartbeat. The sound often gets louder just before the heart begins to contract.

The exam may also reveal an irregular heartbeat or lung congestion. Blood pressure is most often normal.

Narrowing or blockage of the valve or swelling of the upper heart chambers, or their complications, may be seen on:

- Chest x-ray

- Echocardiogram

- ECG (electrocardiogram)

- MRI or CT of the heart

- Transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE)

Treatment

Treatment depends on the symptoms and condition of the heart and lungs. People with mild symptoms or none at all may not need treatment. For severe symptoms, you may need to go to the hospital for diagnosis and treatment.

Medicines which can be used to treat symptoms of heart failure, high blood pressure and to slow or regulate heart rhythms include:

- Diuretics (water pills)

- Nitrates, beta-blockers

- Calcium channel blockers

- ACE inhibitors

- Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs)

- Digoxin

- Medicines to treat abnormal heart rhythms

Anticoagulants (blood thinners) are used to prevent blood clots from forming and traveling to other parts of the body.

Antibiotics may be used in some cases of mitral stenosis. People who have had rheumatic fever may need long-term preventive treatment with an antibiotic such as penicillin.

In the past, most people with heart valve problems were given antibiotics before dental work or invasive procedures, such as colonoscopy. The antibiotics were given to prevent an infection of the damaged heart valve. However, antibiotics are now used much less often. Ask your provider whether you need to use antibiotics.

Some people may need heart surgery or procedures to treat mitral stenosis. These include:

- Percutaneous mitral balloon valvotomy (also called valvuloplasty). During this procedure, a tube (catheter) is inserted into a vein, usually in the leg. It is threaded up into the heart. A balloon on the tip of the catheter is inflated, widening the mitral valve and improving blood flow. This procedure may be tried instead of surgery in people with a less damaged mitral valve (especially if the valve does not leak very much). Even when successful, the procedure may need to be repeated months or years later.

- Surgery to repair or replace the mitral valve. Replacement valves can be made from different materials. Some may last for decades, and others can wear out and need to be replaced.

Children often need surgery to either repair or replace the mitral valve.

Outlook (Prognosis)

The outcome varies. The disorder may be mild, without symptoms, or may be more severe and become disabling over time. Complications may be severe or life threatening. In most cases, mitral stenosis can be controlled with treatment and improved with valvuloplasty or surgery.

Possible Complications

Complications may include:

- Atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter

- Blood clots to the brain (stroke), intestines, kidneys, or other areas

- Congestive heart failure

- Pulmonary edema

- Pulmonary hypertension

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your provider if:

- You have symptoms of mitral stenosis.

- You have mitral stenosis and symptoms do not improve with treatment, or new symptoms appear.

Prevention

People with abnormal or damaged heart valves are at risk for an infection called endocarditis. Anything that causes bacteria to get into your bloodstream can lead to this infection. Steps to avoid this problem include:

- Avoid unclean injections.

- Treat strep infections quickly to prevent rheumatic fever.

- Always tell your provider and dentist if you have a history of heart valve disease or congenital heart disease before treatment. Some people may need antibiotics before dental procedures or surgery.

Alternative Names

Mitral valve obstruction; Heart mitral stenosis; Valvular mitral stenosis

References

Carabello BA, Kodali S. Valvular heart disease. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 60.

Chandrashekhar YS. Mitral Stenosis. In: Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, Bhatt DL, Solomon SD, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 75.

Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2007;116(15):1736-1754. PMID: 17446442 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17446442/.

Writing Committee Members, Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;162(2):e183-e353. PMID: 33972115 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33972115/.

Review Date 2/27/2024

Updated by: Thomas S. Metkus, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine and Surgery, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.